Return to William Free at Mount Hesse

Return to William Free in Melbourne

Return to Free Family in England

Return to First Families Home Page

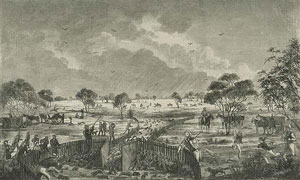

Wimmera sheep station, c1851

The first white people moved into the area around Corack (or Corack East as it is also called) in the 1840s following the establishment of the Corack and Banjenong sheep stations there. At that time the area was known as 'Bald Hills', so named because of the bare ridges that ran beside the road that would later connect Corack to Donald. The Corack station was around 100,000 acres in size and was owned by a series of people including, from 1870 to 1882, a Samuel Craig (who subsequently sold the property to Edward Perry and his two sons Frank and Henry). Working for Craig at the time was a boundary rider, John Shepherd, whose daughters would later marry William Free's sons Samuel and James (see below). According to Jenni Campbell, one of the major tasks of the shepherds and boundary riders alike during this time was to prevent the sheep on the station being stolen by aborigines:

As sheep numbers increased the native game disappeared and the aborigines were forced to spear sheep for food. They developed quite a liking for mutton chops, so boundary riders were hired to watch the flocks by day, and by night the sheep were driven into yards consisting of movable hurdle type fence panels where they were guarded by shepherds. As the boundary riders retaliated against these killings, bad feelings against the aborigines grew and the late Mrs Jane Cook (a daughter of the boundary rider John Shepherd) remembers the Richardson and Morton plains aborigines being rounded up and taken to the Ebernezer Mission at Antwerp (1997: 8-9).

As elsewhere in Victoria, the 1869 Land Act broke up the squatter's holdings and opened the way for working people to select land for farming. According to R. P. Falla, 'the first land to attract attention' in the parish of Corack East was the 'area situated as close to Lake Buloke as possible and fronting onto the surveyed three chain road'. Falla continues that between 1873 and 1875 nearly half of all the land available for selection was taken by such pioneer settlers as William Boothman, John Louttit, Edward Perry and his sons and the aforementioned John Shepherd. 'After 1875', Falla continues, the rate of 'selection declined...as more attractive land could be found elsewhere'. As a consequence the parish was not fully settled until the late 1880s.

Establishing farms in the area would prove no easy task. The Land Act required the selector to live on and fence his or her allotment and to cultivate at least a third of it within the first three years of occupation. The selector was also required to 'pay an annual rental of two shillings per acre which, after three years, entitled him to a lease, and at the end of a ten year period or full payment of £1 per acre, the issue of a Crown Grant' (Falla 1992). The task was compounded by the fact that much of the country being settled was heavily timbered and, as the Cornishman James Lander who settled on land near Mount Jeffcott recounted, 'infested with kangaroos [and] dingos and over-run by squatters' sheep'. These had to be driven off and the timber cleared by chopping down the smaller trees and ring-barking the remainder. Tree roots were dug out using picks and shovels although those settlers who had them used bullock teams or soil grubbers which were also known as 'forest devils' (Campbell, 1997: 9).

Establishing farms in the area would prove no easy task. The Land Act required the selector to live on and fence his or her allotment and to cultivate at least a third of it within the first three years of occupation. The selector was also required to 'pay an annual rental of two shillings per acre which, after three years, entitled him to a lease, and at the end of a ten year period or full payment of £1 per acre, the issue of a Crown Grant' (Falla 1992). The task was compounded by the fact that much of the country being settled was heavily timbered and, as the Cornishman James Lander who settled on land near Mount Jeffcott recounted, 'infested with kangaroos [and] dingos and over-run by squatters' sheep'. These had to be driven off and the timber cleared by chopping down the smaller trees and ring-barking the remainder. Tree roots were dug out using picks and shovels although those settlers who had them used bullock teams or soil grubbers which were also known as 'forest devils' (Campbell, 1997: 9).

Once an area was cleared the settler would dig an earth dam (known colloquially as a 'tank') into which water after rain could run, erect fences to keep out the kangaroos and other marauders, and plant his or her first crops. In his first year Lander 'got in 20 acres of wheat...and after saving my seed for the next year and a bit of hay, had twenty bags to cart to Ballarat for sale'. He received the pleasing sum of four shillings per bushel and 'got a load of potatoes to sell on my way home' ('The Pioneering Life of James Lander', p.3). One of William Free's future neighbours at Corack, Richard Reilly who had selected land there in 1874, cleared seven acres in his first year and also sowed it with wheat. By the end of the following year he had cultivated another four and a half acres, and the year after that 'a further 19 acres sown to oats, barley and peas'. Reilly's and the other settlers' first crops were sown by hand, the seed 'covered by harrowing or in some cases dragging branches of trees'. The crops were also harvested by hand, using simple reaping hooks or scythes (Campbell, 1997: 11).

When these essential tasks were well advanced, the settler could begin constructing a more permanent home to replace the tents and makeshift shelters he and his family were living in. These were usually bark huts of the kind built by the squatters and their shepherds during Victoria's earlier pastoral age. In places where there was a scarcity of timber, the houses were made of mud bricks built over a frame of wooden poles. Their roofs were thatched with grass and, if more than one room were needed,

...they would be partitioned off with bag and bark walls on which pictures from illustrated magazines or often simply newsprint was pasted to give some sort of finish. Beds were simple 'poles laid side by side on cross-pieces supported by stakes driven into the ground, with straw mattresses and some worn-out bed-clothes'. There might be packing cases used as wardrobes and a dressing table. Kerosene tins cut lengthwise or across were put to all manner of uses. Cups and plates were often of tin. These were the bare essentials of a selector's hut, but a family might have its own small treasures—an extra table, a rocking chair, and a woman's most cherished possession, a Singer or Wilcox and Gibb sewing machine (Kiddle, 1963: 419).

The success of the selectors depended on a range of factors that extended beyond their undoubted capacity to work hard. These included adequate rainfall, a familiarity with basic farming techniques and the ability to apply these to the local conditions, and access to capital and labour, where those like William Free who had children old enough to work enjoyed a decided advantage. Luck and timing also played their part. The relatively good seasons that occurred before 1876 enabled many of the early settlers to pay off their debts and purchase their land before the harder times arrived. This was certainly so in the case of John Shepherd who eventually expanded his holdings beyond his initial 320-acre allotment and died, in Corack in 1918, a relatively rich man, leaving his wife and daughters property worth over £63,700 as well as £61,475 in cash (Donald Times, 26 April 1918). Many of those who came later to the district, by contrast, found it harder to meet their commitments and were forced to borrow money at 10 per cent interest from storekeepers, merchants and other money-lenders. As the hard times continued, their debts mounted to the extent that by June 1878 'about one third of the selectors who had received their Crown grants had parted with their land' (Powell, 1970: 180-1).

Whether eventually successful or not, the lives of the early settlers were both hard and heartbreaking, rendered more difficult still by a range of natural and man-made hazards. These were well described by Margaret Kiddle as follows:

Selectors even more than squatters suffered the ravages of scab and 'ther ploorer' (pleuro-pneumonia) for they lacked the resources to battle with them. Their crops were afflicted with grub and blight; their wheat smitten by rust. When conditions seemed to be improving they were eaten out by recurring hordes of caterpillars. Rabbits, like poverty, were always at their doors. If the squatters suffered from the pest, the sufferings of the selectors were a thousand times worse. The rabbits ate the best grasses and left the weeds, they devoured the crops, dug up the potatoes and ring-barked the fruit trees. It was impossible for the selector to put aside fodder in the flush season to be used in the winter, for the marauding army ate everything in sight (Kiddle, 1963: 421).

Such trials resulted in many of the original settlers being foreclosed on by storekeepers or money-lenders, or being forced to sell their land or leases either to neighbours or newcomers. Others hung on tenaciously managing to eke out a precarious, and often squalid, existence. Adults and children alike slaved long hours for little return. In their spare time they worked for the squatters or other landowners while simultaneously, in many cases, stealing or 'duffing' their sheep and cattle. Some, like Ned Kelly and his followers, turned to more violent pastimes which were followed with great interest and anticipation by their less adventurous counterparts. Altogether they formed an underclass of poor and tenanted farmers who, until the turn of the century, informed the settler stereotype that was held by squatters, townspeople and bushmen alike: 'ignorant of farming, lazy at their work, and, because they lived from hand to mouth, "the worst taskmasters and the poorest payers"' (Waterhouse, 2000: 217).

Such trials resulted in many of the original settlers being foreclosed on by storekeepers or money-lenders, or being forced to sell their land or leases either to neighbours or newcomers. Others hung on tenaciously managing to eke out a precarious, and often squalid, existence. Adults and children alike slaved long hours for little return. In their spare time they worked for the squatters or other landowners while simultaneously, in many cases, stealing or 'duffing' their sheep and cattle. Some, like Ned Kelly and his followers, turned to more violent pastimes which were followed with great interest and anticipation by their less adventurous counterparts. Altogether they formed an underclass of poor and tenanted farmers who, until the turn of the century, informed the settler stereotype that was held by squatters, townspeople and bushmen alike: 'ignorant of farming, lazy at their work, and, because they lived from hand to mouth, "the worst taskmasters and the poorest payers"' (Waterhouse, 2000: 217).

Before attending their school classes, the settlers' children would usually spend time collecting firewood, grubbing or fencing, or accompanying their fathers or older siblings as they checked and reset the string of rabbit traps laid at the entrances of the burrows that dotted the properties. In the evenings, their chores completed, they would hunt opossums, go bird-nesting or, as recounted by P. J. O'Donohue whose father selected land at Swanwater in 1873, join their parents in sitting

...around reading - if not books, then the local newspapers and the Weekly Times or Australasian. I don't think we used to get the Melbourne daily papers. Sometimes we played cards or went to a neighbour's place; the linoleums would be rolled back and we would dance on the floorboards to the concertina or violin (cited in Palmer, 1999: 240-1).

While many selectors failed many also, slowly but surely, succeeded. They were aided by the appearance of mechanical stripping, reaping and mowing machines, more suitable ploughs and fencing materials, and a torrent of farming advice propagated in the pages of the ever-expanding rural press.  Over time their crop yields and living standards gradually improved. Tents and bark huts were replaced by weatherboard or brick houses with wooden floors and ceilings, glass windows and galvanised iron roofs. Windmills and corrugated iron water tanks stood nearby. Homes were encircled by fenced-in gardens filled with flowers, vegetables and fruit trees. Grape or passion-fruit vines trailed along covered verandas. Trees formed windbreaks or lined dusty driveways. And carts and drays were complemented by handsome buggies in which the settlers would drive fortnightly into town to meet up with friends and acquaintances and collect their mail and supplies. This had a dramatic effect on the landscape. As one observer of the area around Yawong Hill noted, the plains that a short time earlier 'had all the appearance of the wilderness' are 'now studded with neat and pretty cottages and prosperous farms. Roads where a few years ago you would occasionally meet a swagman toiling along under his bedding, or the lonely stockman, are now alive with vehicles of every description' (cited in Palmer, 1999: 234).

Over time their crop yields and living standards gradually improved. Tents and bark huts were replaced by weatherboard or brick houses with wooden floors and ceilings, glass windows and galvanised iron roofs. Windmills and corrugated iron water tanks stood nearby. Homes were encircled by fenced-in gardens filled with flowers, vegetables and fruit trees. Grape or passion-fruit vines trailed along covered verandas. Trees formed windbreaks or lined dusty driveways. And carts and drays were complemented by handsome buggies in which the settlers would drive fortnightly into town to meet up with friends and acquaintances and collect their mail and supplies. This had a dramatic effect on the landscape. As one observer of the area around Yawong Hill noted, the plains that a short time earlier 'had all the appearance of the wilderness' are 'now studded with neat and pretty cottages and prosperous farms. Roads where a few years ago you would occasionally meet a swagman toiling along under his bedding, or the lonely stockman, are now alive with vehicles of every description' (cited in Palmer, 1999: 234).

As life on the selections became more settled and predictable, following a regular cycle of ploughing, sowing, planting, top-dressing and harvesting, the people in the district began to look beyond their own needs to those of the local community. All across the region bush townships were constructed or rejuvenated with newly-built shops and churches, schools and parks, and to the regret of the evangelists in the community, hotels and billiard rooms. Corack was no exception to this rule. Primary schools were established to serve the communities at Corack North (in 1877) and Corack East (1879). The Corack North State School, pictured below, began with 36 pupils while the first class at Corack East had only only six (this number had grown to 43 by 1880). Between 1877 and 1923 five primary schools had been established in the area. None are there now. By the late 1880s, the Corack township boasted a range of shops, churches and other buildings. The last included a creamery and a town hall and Mechanic's Institute which opened in 1886 with a grand concert and supper dance that continued on until daylight. As Jenni Campbell describes in her 1997 monograph, The Cream of Corack, the town hall was much used and loved. 'Methodist tea meetings proved very popular ... [and] travelling picture shows and concert parties ... were always well attended' (p. 19).

The Mechanics' Institute at Corack

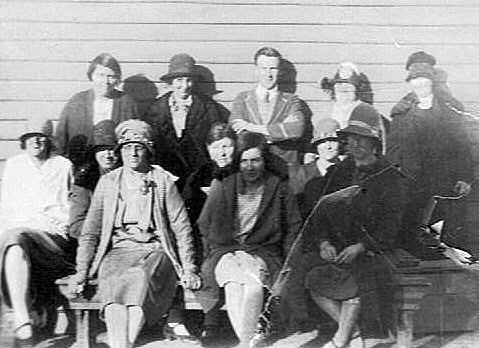

This photograph shows the female congregationists of the Corack Methodist Church in 1929. Alice Martha McCallum nee Free

is second from the right in the front row. On Alice's right is her sister-in-law Joanna Free nee Shepherd.

The photo also includes two of Johanna's sisters: Elizabeth Shepherd (second from the left in the rear row), and

Mary Jane Cook nee Shepherd (fourth from the left in the front row).

Taken on the same day, this photograph shows some of Corack's original settlers including Alice Martha McCallum

and the Shepherd sisters. We think that the man second from the left at the back may be Samuel Free.

In accordance with the Victorian maxims of the time, women played a major role in such community-building; supporting, breeding and nurturing while the men laboured on their farms and ran the district's affairs through such assumed positions of authority as shire councillor, church and parish elder, and president of various lodges and agricultural and sporting associations. Unless they contained large enclaves of miners or other non-agricultural labourers, most rural communities tended also to be politically, socially and sexually conservative, provincially inclined, and generally respectful and respectable. Their denizens believed in salvation and God's will, could be very generous to those among them who had fallen on hard times, but were often disapproving of any who 'failed to help themselves', or displayed unwarranted frivolity, indulgence or independence of mind. Although they enjoyed family and church gatherings, watching and playing sport, and dancing under the right circumstances, they could also be priggish and perversely self-denying. The older generations also remained connected imaginatively as well as sentimentally to their places of origin and sought, through various ways and means, to replicate their English or Scottish 'homes' in Australia. In these ways they served generally to reinforce rather than challenge or alter the colony's prevailing pro-British and pro-imperial values and culture.

The settlers' children, by contrast, were tied less to the places of their parents' and grandparents' imaginations and more to the land on which they lived, played and worked. As Margaret Kiddle enthused, this resulted in them, when young, being generally less inhibited and more carefree and high-spirited than probably their parents were at the same age.

They took joy in the things beloved by all Australian children. They might have to help milk cows and tend other stock, but in spring in open country they watched for the first blue orchids and in sheltered places sought greenhoods. They climbed hollow trees to find parrots' nests and made the young their pets. There were times when they could fish the creeks for yabbies and on summer evenings sit, bare toes in the water, listening to the croak of frogs and the shrilling of crickets. They could hunt wallabies, 'possums and bears, and make rugs from their skins as the aborigines had done. They trapped rabbits and tiger cats. These rough-haired, brown-legged children made the country there own and were themselves part of it (Kiddle, 1963: 428).

As they grew older and more confident, they became less deferential to the district's authority figures, more inclined to challenge their parents, and, as Norman Lindsay captured so nicely in his 1930 novel Redheap (which was banned for a time in Australia), were more disposed towards skylarking and mischief-making or what the more censorious in the community decried as larrikinism. They were, as a consequence, more likely than the older generation to identify with the radical (but still racialised) images and ethos of Australia and Australians then being advanced by the 'Bulletin school' and its urban intellectuals.

* * * * * *

What of William and Eliza Free and their family over this time? R. P. Falla's mimeograph, 'The Selectors in the Parish of Corack East', lists William as one of the original selectors in the area, having been granted a licence for allotments 11 and 14 on 1 July 1878. These were adjoining blocks covering some 264 acres of farming land and located a few miles to the west of the Corack township. On their northern border were allotments 16 and 17 which had been settled in February 1875 by John Shepherd, a farmer who hailed from Ballarat East, and whose daughters, Fanny and Johanna, would later marry two of William and Eliza's sons (see below - John and his wife Johanna are pictured on the right). According to Falla's mimeograph, John Shepherd would also assume, in 1891, the lease to William's allotment number 14. The lease to his allotment 11 was acquired in 1900 by James Lavery, the son of another original settler, Bernard Lavery, who had come from Waubra and settled in the area in 1874.

What of William and Eliza Free and their family over this time? R. P. Falla's mimeograph, 'The Selectors in the Parish of Corack East', lists William as one of the original selectors in the area, having been granted a licence for allotments 11 and 14 on 1 July 1878. These were adjoining blocks covering some 264 acres of farming land and located a few miles to the west of the Corack township. On their northern border were allotments 16 and 17 which had been settled in February 1875 by John Shepherd, a farmer who hailed from Ballarat East, and whose daughters, Fanny and Johanna, would later marry two of William and Eliza's sons (see below - John and his wife Johanna are pictured on the right). According to Falla's mimeograph, John Shepherd would also assume, in 1891, the lease to William's allotment number 14. The lease to his allotment 11 was acquired in 1900 by James Lavery, the son of another original settler, Bernard Lavery, who had come from Waubra and settled in the area in 1874.

Between 1878 and 1900 William and his sons would, like all those who first came to the area, have cleared, fenced, tilled and cultivated their land. They would have built a house for the family to live in and, over time, the stables and other buildings needed to support their farming pursuits. Like Richard Reilly they would have planted wheat and other crops any profits from which would be used to pay off their lease. Given the relatively small size of their holding, and the number of people it had to support, it is likely they would have struggled to meet their various costs. Following the birth of their youngest son, Ernest Oswald Free at Corack in 1881, William and Eliza had produced no less that fourteen children. Two of these, William (1858-60) and Alexander Free (1868-9) had died young and were buried at Mount Hesse and Buangor respectively (the local cemetery records obtained by Fay Menzel show that Alexander was buried at Buangor on 16 February 1869 while William and Eliza were living at Eurambeen - most likely George Begg's Eurambeen Station which was located at Mount Cole near Beaufort). Their oldest son, John Free, had married Mary King in 1878 at Carchap (near Clear Lake in central Victoria) and was living and farming there. Another son, William Free, married Margaret Barbour at Emerald Hill in 1883 and farmed in the area before moving to Pingelly in Western Australia sometime between 1899 and 1909. Their two eldest daughters, Phoebe Ann and Alice Martha Free, had married John Gilchrist and Edward McCallum in 1881 and 1886 respectively, and were no longer living at home (although both were on farms in the Corack area).

This left eight children still at home who, in 1883, were aged between 22 and two years old. While the older boys were able to help William and Eliza with the farm, the younger ones had to be schooled as well as nurtured, an issue their parents seemed not to have taken very seriously. The 13 October 1883 edition of the Donald Express reported that William and a number of others were arraigned before the district court for neglecting to send their children to school for the requisite number of days. In William's case, 'the truant inspector stated that the defendant was continually in default, and asked for a severe penalty. [He was] fined 5s and 5s costs, in default of twelve hours imprisonment'. The same paper reported, on 15 June 1888, that William was fined 2s 6d in the Donald Court of Petty Sessions for the non-attendance at school of his son George. In March 1889 he wrote a letter to the St Arnaud Shire Council 'drawing the Council's attention to the very bad state of road between the properties of Mr John Shepherd and Mr Sands - referred to the engineer with power to act'. This had followed a letter written the previous week 'drawing attention to the bad state of the road between his selection and R. Sands' one-chain road; also between Mr Shepherd's two selections, and another bad place between Mr Fagey and Mr Sands - Engineer to call tenders'.

This left eight children still at home who, in 1883, were aged between 22 and two years old. While the older boys were able to help William and Eliza with the farm, the younger ones had to be schooled as well as nurtured, an issue their parents seemed not to have taken very seriously. The 13 October 1883 edition of the Donald Express reported that William and a number of others were arraigned before the district court for neglecting to send their children to school for the requisite number of days. In William's case, 'the truant inspector stated that the defendant was continually in default, and asked for a severe penalty. [He was] fined 5s and 5s costs, in default of twelve hours imprisonment'. The same paper reported, on 15 June 1888, that William was fined 2s 6d in the Donald Court of Petty Sessions for the non-attendance at school of his son George. In March 1889 he wrote a letter to the St Arnaud Shire Council 'drawing the Council's attention to the very bad state of road between the properties of Mr John Shepherd and Mr Sands - referred to the engineer with power to act'. This had followed a letter written the previous week 'drawing attention to the bad state of the road between his selection and R. Sands' one-chain road; also between Mr Shepherd's two selections, and another bad place between Mr Fagey and Mr Sands - Engineer to call tenders'.

In spite of these day-to-day concerns, by the time of his sixty-first birthday, William Free could look back over his life with some reasonable satisfaction. The poor and uneducated man who had emigrated from Cambridgeshire to Victoria in 1853 and worked as a shepherd at Mount Hesse and Buangor now had sheep and a property of his own. He had survived the rigours and trials of the early settlement era and was now a successful farmer and well-respected member of the district's pioneering fraternity. A number of his children had their own farms and had provided he and Eliza with grandchildren who would, in time, extend his and his family's name and legacy. He still had eight children living at home, but the eldest of these now relieved their father of much of the daily grind of managing a Wimmera block. Probably for the first time in his life, William had time aplenty to tend his horses, meet up with old friends and acquaintances, and attend the local football or race meets. In spite of these achievements William felt dispirited and unsettled, brought on, perhaps, by the financial and other pressures described above. He had also been unwell for the past two years and had recently begun experiencing cramping pains that worried him but about which he declined to see a doctor. As his family later recalled, he had grown quiet and withdrawn and seemed to prefer to get out of the house and off by himself.

On the morning of 2 June 1890 he arose early as usual and put on a clean shirt that Eliza had left out for him. He walked about the kitchen, pulled on a coat to ward off the winter cold and then left the house. At breakfast Eliza said to her son Ernest how is it your father is not in and told him to go and call him. The boy returned saying he could not see him. A second son, James, said he is likely gone down to the stack for a sheaf of hay for his horse. After finishing his breakfast James 'went out and looked towards the stack and could not see him. I then went to the paddock and got my horse. I met my brother Alfred when I came back and asked him if father had gone up to my brother William's place'. Alfred replied 'no I have not seen him for the morning'. James then rode down to the sheep paddock as he

thought he may have gone down there and not seeing him there I went to the hay stack where it was customery [sic] for him to go for horse feed and to feed some of the horses. As I approached the stack I saw his coat hanging on the fence. I got off my horse and looked round and saw a sheaf of hay near the edge of the tank which was close by and next saw a red shirt floating on the water. A rope was attached to the sheaf of hay. I got hold of the roap [sic] and pulled it a shore and found it was tied round my father's neck. I brought him to the bank and found him quite dead. I then got on my horse and galloped home and told my mother and brothers.

The family reported the drowning to the police and Mounted Constable Ryan rode out to the farm to investigate. His report, subsequently read out to the inquest held into William's death, read as follows:

a man named William Free aged about sixty seven [later changed to sixty one] was found drowned in a dam in one of his own paddocks about half a mile from his residence. The deceased complained of being ill for the last couple of days but got up this morning apparently alright he fed some horses that were in the stable near the house and was seen by his son (James) about 7.30am going in the direction of a haystack where there were some more horses to be fed. About an hour after the son had occasion to go to the haystack and on seeing a coat and boots close to the tank he went to look and saw his father in the water. He pulled him out and found life quite extinct he used all the usual means to restore animation but of no avail. I visited the place this afternoon examined the body there were no external marks of violence. I had it removed to his late residence awaiting enquiry I don't think there are any suspicious circumstances in the case the people are respectable and I believe it to be a case of suicide.

Constable Ryans' view was supported by both the local newspaper and the investigating magistrate, a J. P. Meyer who, in the early days and to the consternation of the local squatters, had run a store and grog shanty at the Richardson River near the Banyenong run. As we would expect, William's death was the talk of the neighbourhood, both mystifying and alarming its pious and church-going residents. His death certificate indicates he was buried at the Corack cemetery which lies amidst wheat fields some four miles from the township (and where some believe William and Eliza's son Alexander was buried some twenty years before). The ensuing years have seen the grave, like so many others in the bushland cemetery, fall into disrepair. In 2014 one of William and Eliza's grandsons, Des Menzel, and his wife Fay journeyed from Victor Harbour in South Australia to Corack restore William's grave and add two tombstones that provided details of William (and Eliza's) life and times.

William Free's tombstone. A photo of his and Eliza's grave is shown below.

* * * * * *

As the family sought to come to terms with William's suicide, life continued on. The family farm at Corack was sold to a neighbour and Eliza and the younger Free children went to live in the nearby township of Watchem. On 6 April 1891 William and Eliza's sons, Samuel and James Oswald Free married Fanny Johanna Shepherd and Johanna Shepherd in a double wedding held at the home of the girl's father, and William and Eliza's former neighbour, John Shepherd. The two couples lived initially on separate blocks of land at Corack East. Samuel had purchased his block from his mother while James had successfully applied for his through the local licence board. In October 1895 the Donald Express informed its readers that James had transferred the lease to his 161-acre allotment to Arthur S. Madder of Corack East. Shortly afterwards he and his family (pictured below in around 1911) moved onto land at Lalbert East (or Talgitcha) some 50 miles north of Corack. A few years later Samuel and his growing family also moved to Talgitcha to begin their lives anew.

James and Johanna Free (nee Shepherd) and family at Lalbert East in around 1911

On 7 November 1894, Eliza Free married a local farmer, William Bruce (1828-98) at Watchem. According to their wedding certificate, William was born at 'Arneroach' in Fifeshire in Scotland in around 1828, the son of Henry Bruce, a labourer, and Catherine Herd. The LDS IGI shows that Henry and Catherine were married at Carnbee in Fifeshire on 12 December 1825 and had seven children there in addition to William: Henry (1828), Christiana Robertson (1831), Archibald (1833), John (1838), James Brown (1841) and Anne Bruce (1844). The certificate also shows that at the time of his wedding to Eliza, William was 66 years old, had been a widower since 1888, and had no children. The wedding was witnessed by Eliza's son-in-law, Edward Angus McCullum, and a John Wyles. It is interesting to note that, unlike William and the two witnesses, Eliza signed the marriage certificate with a mark.

In around 1897 two of Eliza's younger sons, Alfred (pictured on the right) and George Bruce Free left the area, Alfred to go horse-breaking and George to try his luck on the Western Australian goldfields. On 29 June 1897 the Donald Times reported in its 'Westralian news' that a 'very painful accident happened to Mr Geo Free, of Corack, quite recently. It appears he was cleaning some engine boilers when his foot became entangled, and he fell heavily into a heap of hot ashes, burning his feet considerably. Assistance was quickly at hand and he is now progressing splendidly'. On 13 July the paper's editor informed his readers that 'Mr G. Free, whose accident was reported in my last, is improving and will be able to return to his duties in the course of a few days'. George also returned to Watchem where, in 1899, he used the profits obtained from his western sojourn to purchase John Casey's farm at Massey as well as a share in the farm of a Mrs S. Stubbs of Watchem. George married Martha Clara Vogel (pictured below in the buggy with her future mother-in-law Eliza Bruce) at Watchem in 1902 and later went with her and their family to live and work on Victoria's Mornington Peninsular. Click here to read of George and Martha's life, times and family.

In around 1897 two of Eliza's younger sons, Alfred (pictured on the right) and George Bruce Free left the area, Alfred to go horse-breaking and George to try his luck on the Western Australian goldfields. On 29 June 1897 the Donald Times reported in its 'Westralian news' that a 'very painful accident happened to Mr Geo Free, of Corack, quite recently. It appears he was cleaning some engine boilers when his foot became entangled, and he fell heavily into a heap of hot ashes, burning his feet considerably. Assistance was quickly at hand and he is now progressing splendidly'. On 13 July the paper's editor informed his readers that 'Mr G. Free, whose accident was reported in my last, is improving and will be able to return to his duties in the course of a few days'. George also returned to Watchem where, in 1899, he used the profits obtained from his western sojourn to purchase John Casey's farm at Massey as well as a share in the farm of a Mrs S. Stubbs of Watchem. George married Martha Clara Vogel (pictured below in the buggy with her future mother-in-law Eliza Bruce) at Watchem in 1902 and later went with her and their family to live and work on Victoria's Mornington Peninsular. Click here to read of George and Martha's life, times and family.

Alfred, meanwhile, had married in 1890, to Emma Tissot at Mount Cole in Victoria, and was later issued with a warrant and subsequently arrested by the Victorian police for horse stealing. After serving 12 months imprisonment at Pentridge Gaol, he and Emma and their daughter, Emma Louise Free, travelled to the Western Australian goldfields at Kalgoorlie. He later farmed land near Pingelly, (to where Alfred's older brother, William Free, and his family had earlier moved), before moving to Perth where his wife Emma died in 1917. Alfred re-married, to Eunice Schmitt, two years later and continued to farm near Pingelly. Click here to read of both Alfred and William's life, times and descendants in the West.

Eliza's second husband, William Bruce, died at Watchem in 1888, leaving Eliza once again a widow. The year after William's death, Eliza's youngest daughter, Mary Ann Free married John William Donnan at Watchem. The ceremony, said by the Donald Times to involve 'a pleasant gathering of relatives and friends', took place at Watchem and was followed, the newspaper report continued, by a wedding breakfast held at the residence of the bridegroom's mother. After their marriage John and Mary Ann lived initially on a 250-acre block of land, known locally as Mooney's, at Sammy's Lake near Watchem before, in 1910, moving to Willangie in the northern Mallee region. You can read about their life and times at Willangie by clicking on the above link.

Among the many guests at Mary Ann's wedding would have been Eliza's two youngest sons, Benjamin and Ernest Oswald Free, who were then both living and working at Watchem. In the early 1890s Benjamin worked as a labourer as well as being a steward for the Corack Turf Club. The electoral rolls indicate that he and Ernest farmed land in the area from at least 1903 until the end of the First World War. During this time, Benjamin continued to contribute to the local community - donating 2/6 to a collection for the Dickie family in 1904 and 10s to the Spicer fund in 1906 - as well as maintain and upgrade the farm and its surrounding infrastructure (on 17 February 1914 the Horsham Times reported that the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission had awarded B. Free and Co. of Watchem a contract by for the 'construction of about 14 miles [of the] main eastern channel').

In 1906 Ernest married Adeline Ellen Bennett, the daughter of Jonathon Bennett and Eliza Emily Tout, at the nearby township of Donald. After their marriage Ernest and Adeline lived on their farm at Watchem and had seven of their eight children there before selling up and leaving the district in 1917. Click here to read of their subsequent life and times.  By this time Benjamin seems to have gotten into financial difficulties as well as have some sort of falling out with his mother Eliza (pictured in the buggy with her daughter-in-law Martha Free nee Vogel). The Court Report in the 14 May 1917 edition of the Donald Times informed its readers that 'at the local police court last Friday a case was heard to determine the ownership of goods seized by Waddell & Co. from Benjamin Free, of Watchem. Miss Pomeroy appeared as the claimant. After a lengthy argument the bench found in favour of the defendants and allowed 6 pound 1 shilling costs against the claimant. In a second claim by Mrs Bruce (mother of Free) the claim for furniture was allowed, but with regard to a horse, the bench decided it was the property of Free and found in favour of defendants'.

By this time Benjamin seems to have gotten into financial difficulties as well as have some sort of falling out with his mother Eliza (pictured in the buggy with her daughter-in-law Martha Free nee Vogel). The Court Report in the 14 May 1917 edition of the Donald Times informed its readers that 'at the local police court last Friday a case was heard to determine the ownership of goods seized by Waddell & Co. from Benjamin Free, of Watchem. Miss Pomeroy appeared as the claimant. After a lengthy argument the bench found in favour of the defendants and allowed 6 pound 1 shilling costs against the claimant. In a second claim by Mrs Bruce (mother of Free) the claim for furniture was allowed, but with regard to a horse, the bench decided it was the property of Free and found in favour of defendants'.

Benjamin's experience led him to leave Watchem and take up farming in the Parish of Duddo near the Mallee town of Cowangie where his brother, Ernest, and sister, Mary Ann, had earlier re-settled. The electoral rolls and other records sighted by Fay and Des Menzel indicate that Benjamin was by then either married or partnered and that he and his partner, Maud Free, had a daughter, Mavis Free, who was born in 1907 and had attended school at both Watchem and Pallarang (Maud and Mavis are pictured in the photo below). Maud Free disappeared from the local electoral rolls in 1942 and Benjamin in 1949. Although we can't be entirely certain it is him, it seems Benjamin eventually moved to South Australia, died of a heart attack in the Adelaide suburb of Rosewater on 6 April 1961 and was buried at Dudley Park Cemetery in Port Adelaide two days later. His death certificate, a copy of which was obtained by Fay Menzel, describes him as a retired farmer who was born in Victoria in around 1875. Information later given by the cemetery to Darryl Brady indicates that Benjamin's site has no tombstone, no-one else is buried with him and the cemetery has no living contacts on record for it. This together with the fact there was no informant for his death certificate suggests he was living alone at the time of his death.

Photo showing Benjamin's wife/partner Maud Free (centre row third from the left)

and her/their daughter Mavis (seated in front of Maud and to her left)

Eliza Bruce (formerly Free nee Flavell) died in Watchem on 1 Jan 1925, aged 86 years. She was said to have been buried alongside William Free at Corack. Like many who countenanced death in those days, she would probably have expected to join those members of her family who had already 'crossed the divide'. While less certain of its prospects, she would probably have hoped also again to see William in order, perhaps, to ask him why he had done what he did.

The grave in the Corack cemetery of William and Eliza Free which Des Menzel (pictured) and his wife Fay restored in 2014.

(last updated October 2014)

Image sources

'Mr Evans' higher sheep station with Stone Hut Creek, 1851'. Watercolour by George Finch French (1822-1886). National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an6054747.

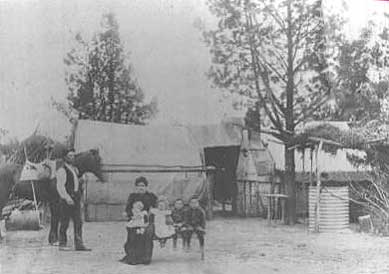

'Selector's hut and family at Tyntynder near Swan Hill'. Courtesy of Fiona Lewis.

'Settler's hut in partially cleared bushland'. From Derrick I. Stone and Donald S. Garden, Squatters and Settlers, (Frenchs Forest: Popular Books, 1978), p. 103.

'Early Settler's Home, 1908'. Oil on canvas by L. Stalker. National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an2287630.

'Rabbit battle at North Corack, 1879'. Wood engraving by F. A. Sleap for the Illustrated Australian News. Australian National Gallery, nla.pic-8926649.

'Reaping hay'. From Derrick I. Stone and Donald S. Garden, Squatters and Settlers, (Frenchs Forest: Popular Books, 1978), p. 161.

'James and Johanna Free and Family'. From Win Noblet, The Hickmott Story 1825-1981 (Bendigo: Cambridge Press, 1981).

'Martha Vogel and Eliza Bruce (nee Free)', courtesy of Cheryl Kerr.

'Alfred Free', courtesy of Helen Murphy.

'1929 Methodist congregation', from Jenni Campbell's monograph the Cream of Corack: 1844-1997 (Red Cliffs, Sunnylands Press: 1997).

William and Eliza's grave and tombstones and 'Maud and Mavis Free', courtesy of Fay and Des Menzel (the people shown in the last photo are: Back (L/R): Mrs Hickman, Mrs A. Gunn, Jack Curley (teacher), Mrs Saltmarsh and Mrs Chatterton. Front from left: Mrs Clarke, Mrs Herb Bennett, Mrs McGough, Mrs Ben Free, Mavis Free, Mrs hetherington and Mrs Copy.

'Corack Mechanics' Institute', 'Corack North State School' and 'Corack Old-Timers' all from photos section of the Wycheproof Historical Society website.

| Rootsweb site for the Free, Flavell, Finkell, Coxall, Chaffe and Shepherd families | William Free in Australia Arrival in Melbourne 1853-1855 |

| William Free in Australia Mount Hesse to the Wimmera 1856-1878 |

Family and ancestors of Eliza Free nee Flavell (1840-1925) |

| Return to First Families Index |

Return to First Families Home Page |